|

The study authors

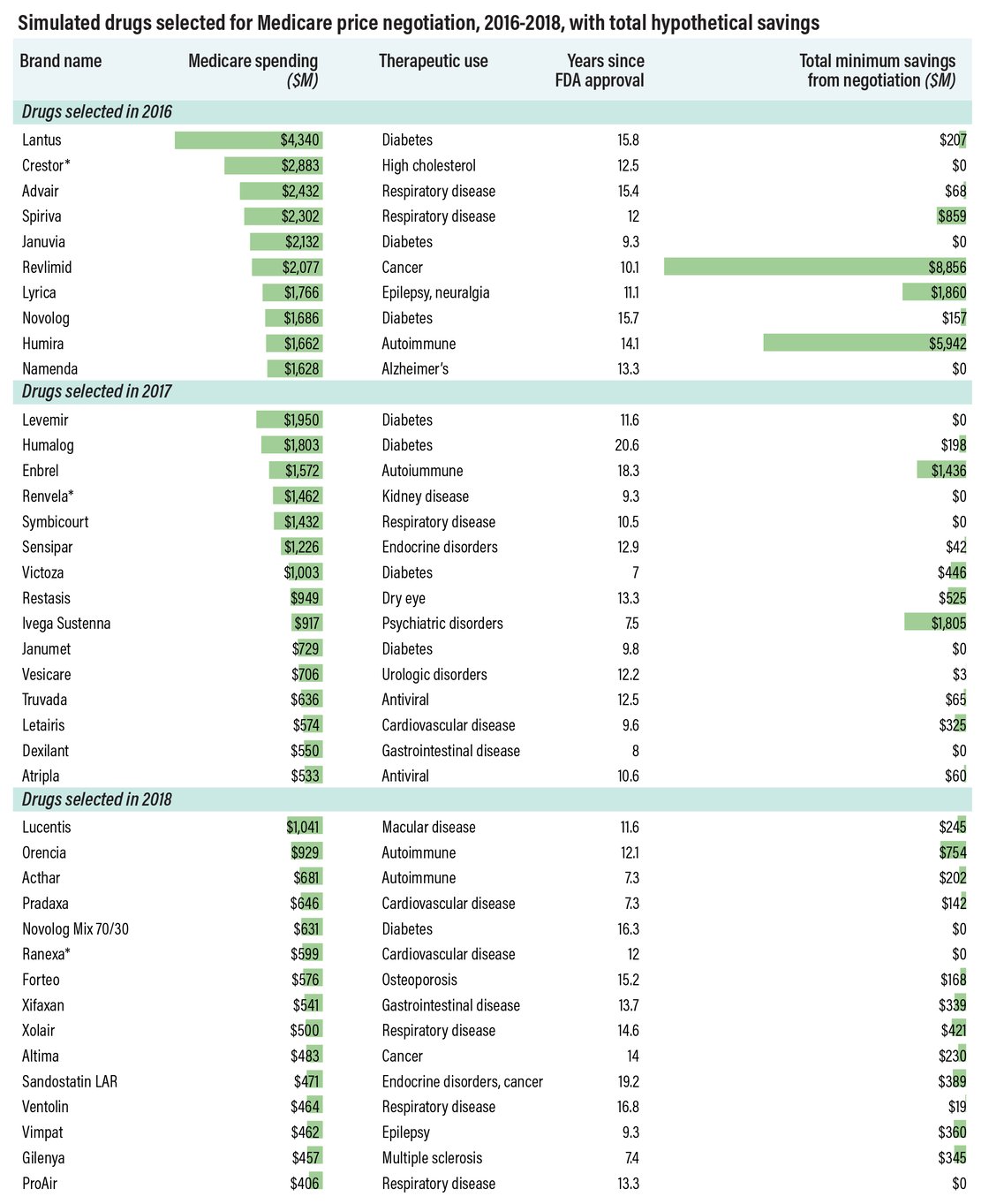

pointed out that such a stringent selection process will hamper savings

potential. Drugs must be chosen in order of highest spending, which could

create missed opportunities if costlier therapies get generic competition

before a negotiated price goes into effect. This happened with three

drugs in the simulation: Crestor, Renvela and Ranexa (see chart, below).

Meanwhile, drugs like AbbVie’s Humira and Pfizer’s Lyrica generated some

of the greatest savings ($5.9 billion and $1.9 billion, respectively) in

the simulation, but they won’t be eligible for price negotiation in the

real world. That’s because Lyrica’s first generics launched in 2019, while Humira’s first biosimilar,

Amgen Inc.’s Amjevita, launched last month, with more to follow.

The study authors also

noted that negotiation could create “unanticipated market effects” if CMS

selects one drug in a particular class, but not another. Manufacturers

could feel pressured to match government-negotiated prices, but they

could also leverage payer rebates to maintain higher prices. This “could

create situations in which negotiated rebates for non-selected drugs

encourage Part D plans to offer a preferred formulary position for

non-selected competitors carrying higher prices for patients,” the

authors wrote. Drugmakers could also launch new formulations of existing

products to avoid selection.

|

No comments:

Post a Comment